As discussed in the first part of this series, the Woodland Period Cultures inhabited a vast amount of pre-contact North America, essentially all of Eastern North America. Likewise, it encompassed a significant length of time, spanning 2,000 years from 1000 B.C. to A.D. 1000, give or take some centuries, which overlapped with the more recent Mississippian cultures. The Late Woodland period, which this site is associated with, spans from A.D. 500-1000.

George Quimby, the anthropologist who studied and analyzed the site and its artifacts, dated the organic materials in the burials to the early 17th century, but recognized the occupation of the site may be older, though how long indigenous populations had been living in and around the site is anyone’s guess.

As mentioned before, the significance of this site is in the sliver of history it occupies - just a handful of decades before European contact - as indicated by the lack of any foreign trade goods present at other sites.

This culture - creatively designated by Quimby as “the Dumaw Creek culture” - was likely a precursor to the Algonquian-speaking Potawatomi, though Quimby also names the Sauk and Kickapoo as just as likely. The people of Dumaw Creek would have been hunters, gatherers and farmers, with evidence of all three present at the site.

We also see from the evidence of bison hides and copper ornamentation that the culture also had established trade throughout the Great Lakes, or at least from southwest Michigan to the Upper Peninsula. As to be expected, trade was highly reliant on water. Though the site borders the creek, folks familiar with the area will recognize that the waterway is shallow and not easily traversed, and is a good mile’s hike away from the nearest area one could feasibly float a canoe. While, again, it's difficult to know what the site may have looked like 400 years ago, it was Quimby’s opinion that this section of the creek did not serve any navigational purpose.

The construction of the village itself Quimby based on settlements near Lake Huron in Ontario during the 17th century, comparing the similar environments and cultural markers of the two. The village was likely fortified, with walls of sharpened posts, and dwellings were likely oval-shaped, domed wigwams constructed of wood and other earthen materials.

The village would have been occupied seasonally, ranging from early spring to late autumn, judging by the presence of wild grapes and pumpkin seeds (which ripen in spring and autumn, respectively). During the winter, Quimby posits they would have migrated inland or south, hunting elk in the forests or bison in the prairies. Even though the Dumaw Creek people wouldn’t have had to deal with driving cars in lake effect snow, I can’t blame them for wanting to get out of Dodge in the winter.

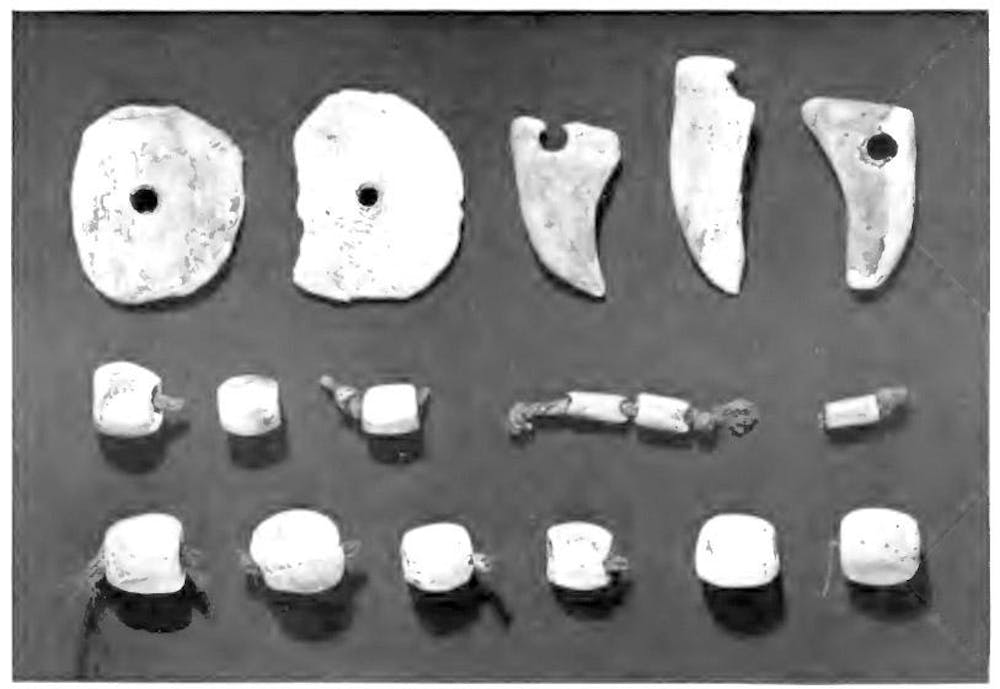

Evidence on the type of dress the Dumaw Creek culture would’ve worn is incomplete, as textiles are notoriously degradable. What was preserved in the burials are the ornamentation (made of copper and shell) and robes and blankets made of animal furs. The furs in particular consisted of beaver, elk, bear and raccoon, and the outward-facing sides were decorated with ochre to create curvilinear designs. Considering the dress of other contemporary native cultures that do survive, the blankets would have likely been paired with moccasins, shirts and leggings of prepared animal skins. Ornamentations consisted of hair pipes, beads and necklaces of copper and shell. Some likely also wore headdresses of feathers and wore clothing or bags with fringes on which they fastened copper beadwork, which is a fashion choice I can definitely get behind.

The material objects at the site, both in the burials and at the village, suggest a wide variety of household tools that the peoples would have used, from mussel shell utensils, axes and hatchets, and woven and clay vessels to items used to scrape animal skins and construct weapons.

Judging by the presence of clay pipes, smoking would have been an integral part of the culture. While there is no evidence of tobacco being grown in Michigan at the time, it was grown in parts of Ontario and could certainly have been obtained through trade. However, even if there was no tobacco, Quimby points out that there were at least 27 different native plants and bark that could have been smoked.

And of course, the burial and death practices of the Dumaw Creek people are very obvious. One or two bodies were placed in individual pits on high ground near water, located about a half-mile from the living spaces. The dead were dressed in their finest attire and wrapped in skins, dusted red with ochre, and buried with tools they either used in life or perhaps would need in the afterlife.

Just as important as the question “Who were the Dumaw Creek people?” is the question “Where are they now?” With all my criticism of the museum world, you can bet your bottom dollar I searched for any indication of the fate of the human remains. To this day, museums are finding literal skeletons in their closet, and some are reluctant to repatriate them, particularly if they belong to a non-white culture.

In 2014, the Department of the Interior put out a press release identifying the human remains and grave goods associated with the Dumaw Creek site in the possession of the Chicago Field Museum and 50 Native American tribal bands, which are possible descendants of the culture. The release also identified the day on which the Field Museum would transfer the remains and their artifacts to the named tribes - March 8 of that year.

Surprisingly, in the over 50 years since Quimby’s study, no other records indicate that any anthropologists or archaeologists have revisited the site or the people who lived there.

Today, there is a nature preserve on Dumaw Creek. A lot has changed in the last 400 years, but there’s no shame in walking the riverbed and imagining the village and its people.