In the initial reports of the site, 19 complete burials were discovered at the Dumaw Creek Site, with newspaper articles describing how “all bodies faced the east, and had been buried in a sitting position, with knees drawn to the chest.” Initially, the newspaper article drew comparisons between the positioning of the Dumaw Creek bodies and burial remains found in Central and South American indigenous groups, such as the Aztecs or Incas, and posited those cultures may have once resided here. However, the author of the 1966 report from the Field Museum, George Quimby, asserts that the bodies were likely positioned lying on their backs or sides, as is commonly seen in other burials from the Late Woodland cultures.

Far be it from me to tell anyone the most efficient position in which to bury a body - I just explore graveyards, not add to them.

During the discovery of Dumaw in 1915, 19 bodies (primarily partial skeletons) were discovered, and 14 of them made their way to the Field Museum. However, it's estimated that as many as 55 individuals were buried and subsequently removed from the site, whether by Schrumpf or other local individuals who dug at the site independently.

From the 14 partial skeletons the Field Museum could access, researchers were able to determine the gravesite contained individuals of a variety of ages, from toddlers to adults, with both sexes present.

The most fascinating (and macabre) detail about the bodies was that several of the male skills still had hair attached to the scalp. The hair was colored a reddish hue from ochre, though it is unclear whether that was intentional or a byproduct of ochre being present amongst the grave goods. Likewise, the hair was heavily ornamented with beads and piping made from copper and shells. Many of the bodies were wrapped in furs.

While Quimby had access to the inventory of the site made by Schrumpf and the University of Michigan, the context and placement of the grave goods in relation to the persons were not recorded. Unfortunately, this means that quite a lot of information regarding the objects, their significance and purposes is lost.

The grave goods included in the Dumaw Creek Site burials, as well as what objects were found within the boundaries of the village site, can still tell us a wealth of information about what materials the native peoples had access to and what could be made from them.

While the Field Museum’s Department of Zoology, who’d originally purchased the Nelson collection, was not willing to deal with the nightmare that is the accidental discovery of human remains in museum storage - they were helpful in identifying the animal furs, skins, bones and teeth buried at Dumaw. These animals include black bear, beaver, buffalo, deer, elk, raccoon, weasel and freshwater mussels, as well as a beak of what may be a species of hawk. While most of these animals were once plentiful in West-Central Michigan during the habitation of the site, buffalo were found only as close as the prairies of Southwest Michigan, some 200 miles away. This, plus the sheer wealth of copper artifacts (which were found to originate from Northern Michigan), indicates a robust and healthy trading network throughout the Great Lakes Region.

As far as vegetative products present at the site, there are examples of ferns and white pine, as well as arrow shafts made from a variety of reed-type plants. Some few examples of consumable vegetation were wild grapes and pumpkin seeds.

These flora and fauna examples were also made into fabrics, such as woven plant fibers, braided grass and yarn wound from buffalo fur.

The aforementioned copper was used as ornamentation. Dozens of hair pipes (thin copper sheets rolled into long, narrow cylinders, through which hair could be threaded) were found at the site, ranging in length from 3.5-7.5 cm. There were also beads for hair and pendants made from copper and shell. Many of the copper pendants were formed into and engraved with zoomorphic designs, like birds and snakes, with one intriguing example being designated a “weeping eye.” This design essentially resembles a face with crying eyes, and I would be lying if I said I didn’t want a necklace resembling it.

Alongside the more frivolous jewelry were practical stone and bone tools, including over 1,000 arrowheads. The vast majority of these flint arrowheads were shaped into a typical triangle, no longer than 2 cm, with some minor variations in form and a wide variety of colors. Considering the large amount of arrowheads, the discovery of chert (the byproduct of “knapping” and shaping flint tools) was no surprise.

There were also a handful of tobacco pipe fragments made of either stone or clay, many engraved with geometric designs, and a couple formed into long-beaked birds resembling kingfishers or woodpeckers.

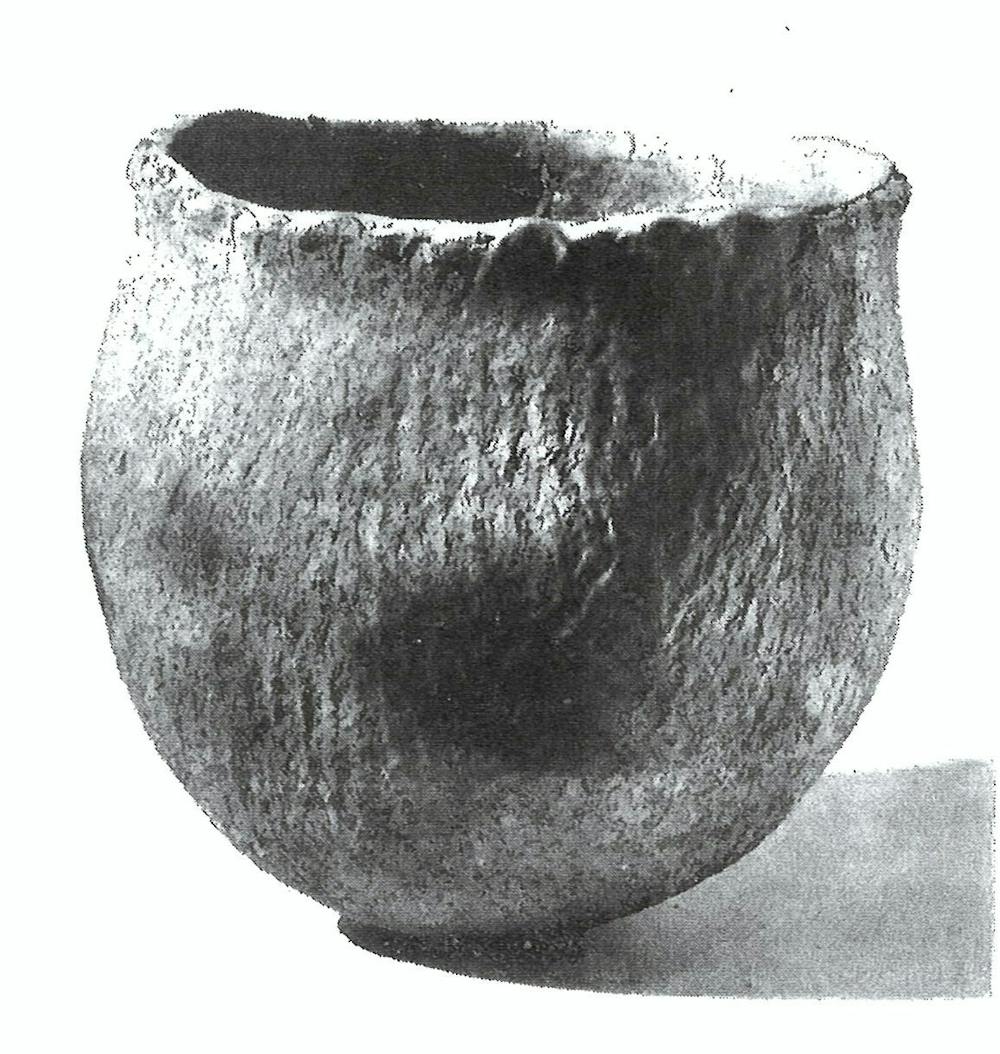

My favorite artifacts, however, were the pottery. Two examples of whole clay pots were uncovered from the gravesites, with plenty more sherds scattered around the village. The whole vessels are round and squat, 18 and 20 cm high, with wide-mouth, flared openings. The pottery was textured with thick fabrics, which would have been wrapped around the pot while still wet. The two whole vessels are red-brown in color, while the sherds come in wider color varieties. My favorite aspect of the pottery are the opening edges, which were pinched into a scalloped design, which Quimby accurately noted resembled pie crusts. The obvious hand-modelling of the pots adds such a stunning, human element to the artifacts, in such a way they cannot be divorced from the bodies found beside them.

As per usual, I’ve gotten far too excited about bits of metal and earthenware, so readers can look forward to the conclusion of the Dumaw Creek Site next week, when I will finally discuss the indigenous cultures of the Late Woodland period, as well as the status of the site, artifacts and remains today.