Back in undergrad, I learned in my museum studies classes that the objects on display at a museum are just a mere fraction of what the institution has in their collection. And to that, what the museum has in their collection that is documented is infinitesimal compared to what is just lying around in boxes - untagged and uncatalogued and often with no indication of where the heck they came from.

That’s one of the museum world’s dirty secrets (of which there are many). Another dirty secret: up until the mid-20th century, historians and archaeologists conducted themselves like cowboys in the Wild West. There were no rules, hardly any standards of ethics, and anything belonging to a people deemed inferior (see: not Western European) was up for grabs and treated like the contents of a Walmart bargain bin.

With a work culture such as this, even the most well-intentioned academics and institutions during this period couldn’t help what slipped through the cracks. This is likely how the findings of a historically significant and rare archaeological site in north Oceana County were nearly lost in a dark corner of museum storage.

The provenance begins in early spring of 1915 when Charles Schrumpf dug up a pine stump on his property, only to discover a grave site containing around 18 bodies and their grave goods. This discovery was made known to the University of Michigan’s Museum of Anthropology and its prominent anthropologist, Dr. Wilbert Hinsdale. Hinsdale, in turn, directed a Mr. F. Vrieland to inventory the discovery for the museum.

The collection stayed with Schrumpf, however, and sometime after 1924, it was sold to H. E. Sargent, a “dealer of stamps, coins, and Indian ‘relics.’” Sargent advertised his collection - which he claimed originated from earthen burial mounds located in Whitehall - throughout the 1920s and 30s, before a large portion was sold to a schoolteacher from Grand Rapids named Charles Nelson.

That brings us to 1958, when the estate of the late Mr. Nelson was purchased by the zoological department of the Field Museum in Chicago. Nelson’s estate primarily consisted of shells and fossils, so imagine the surprise the zoologists had when they encountered arrowheads, pottery sherds, and human remains. Oh, yes, along with boxes of rocks, were several skulls, some of which still had hair attached to the scalp.

Naturally, the zoological department handed that box to the anthropology department, who were better equipped to handle that proverbial can of worms. The Nelson collection became the personal project of the Grand Rapids-born and University of Michigan alum, Dr. George Quimby. As Quimby recounts in his article on the site - published in 1966 in the journal "Fieldiana: Anthropology" - the only two “clues” he had indicating the origin of the collection were the name of the prior owner (Nelson) and that one of the boxes bore the note “Newaygo County, Michigan.”

This scenario is pretty par for the course when it comes to the museum field.

So embarks Quimby on his journey to retrace the origins of the box. After ringing up his Grand Rapids contacts, Quimby came to learn about the original dealer, Sargent, and his advertisement for the collection. If you’ll remember, Sargent claimed that the artifacts originated from Whitehall, which Quimby quickly called bull on, recalling his own childhood spent in Muskegon County without a single mention of an Indian burial mound unearthing.

Thankfully, Dr. Hinsdale of U of M kept thorough records of all known Native American archaeological sites in Michigan, of which Quimby was well aware. The "laborious process” of combing through those records awarded him with an undated newspaper clipping recounting the discovery and correspondence between Hinsdale and Schrumpf, with one letter naming Sargent as the dealer who bought Schrumpf’s findings. After locating photographs of Schrumpf with the artifacts, Quimby was able to finally confirm that the Field’s artifacts were indeed the same.

With the location - Section 5 of Weare Township - confirmed, from 1960-1962, Quimby led a surface collection project, resulting in further finds of pottery sherds and arrowheads, all practically identical to what Schrumpf had found almost half a century before. He was also able to track down other artifacts purchased from Sargent, including a collection from the Michigan Archaeological Society and other private collectors. Quimby also spoke with Seymour Rider, a local Hartian whose own Indian artifact collection is on display at the Hart Historic District. Rider did not purchase from Sargent or Schrumpf but, in fact, dug around the Dumaw Site on his own, resulting in some of his findings, which Quimby purchased for the Field Museum.

With the Dumaw Creek Site found and much of the original collection identified, Quimby and other anthropologists could begin the work of contextualizing the people and artifacts found, which led to another startling discovery.

This site may have been one of, if not the youngest, pre-contact villages of the Late Woodland Native culture era found in Michigan. The Woodland Culture was a pre-Columbian collection of Indigenous North Americans, covering a wide territory of Eastern North America from subarctic Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. They were known for their pottery and burial mounds, the most prominent example being Serpent Mound in Ohio. The Late Woodland period spanned from the years 500 to 1000, and it is likely this people group inhabited the site until 1620, the time of the first European contact in the Great Lakes region. The dating of the site was determined by the age of the tree stump Schrumpf removed, later radiocarbon dating, comparative evidence from other sites and a lack of European trade goods.

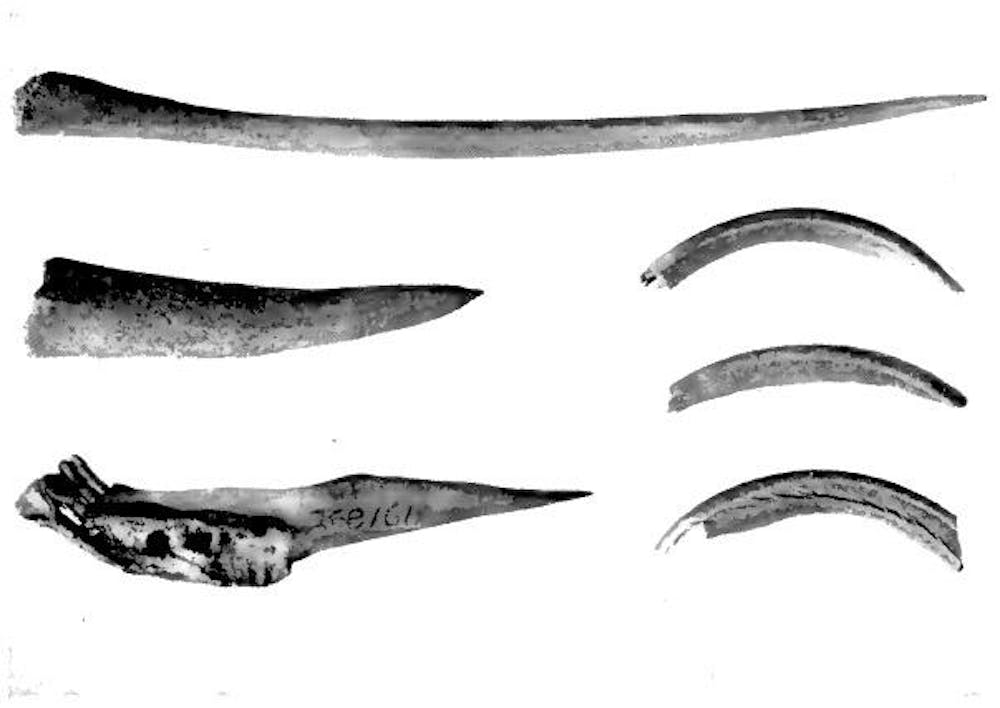

And what a wealth of artifacts there were at the Dumaw Creek Site. I hope you’ll join me next week, where I discuss the findings and what they tell us about the Native peoples who lived in Oceana County before the 17th century.