While this disaster did not happen on any of our local lakes, it did involve a couple of local residents at the time. The following article appeared in the Whitehall Forum Nov. 13, 1884.

The details of the burning of the steamer Maasdam at sea recently, as related by Abram Sant and Ed. Boardwell, the White Lake passengers, furnished a picture of thrilling interest. The following details were gleaned from an interview with Messrs. Sant and Boardwell.

The steamer, which was of 2,200 tons burthen, had been at sea about a week, with a cargo of Holland gin and oil, and 186 souls aboard. One morning at about six o’clock, the doors of the staterooms were opened and the cry of fire startled the ears of the occupants. Everybody turned out pell-mell and was ordered to the upper deck of the boat, where a fearful night met the gaze. The large sky-light openings over the engine room were a mass of seething flames, and the smoke was rolling up in black clouds. It appears that one of the oil tanks had been leaking, and an engineer going to it with an open torch-light had let the light fall into the oil, causing an explosion and filling the engine room with fierce flames. Instantly all was excitement.

As soon as the awfulness of the situation dawned upon the passengers, the air was filled with lamentations, women tore their hair and children screamed. The officers, who were cool and brave, had all they could do to keep the huddling mass of humanity on the upper deck within the bounds of reason. No passengers were permitted to return to their room, and the men were kept busy at the pumps, and carrying water. The only hope of quenching the flames was by throwing the water through the sky-lights, as an open door below would have created a draft and sent the fire through the whole ship; but when it became evident that the flames could not be checked and that the ship must go, the life-boats were ordered lowered, and then scenes of the wildest excitement were enacted among the passengers. One man drew a knife and raised it to strike himself, when the captain knocked him down and took the weapon from him. A woman with two children, when the doors finally swung open, started into the smoke and flames, but was brought back. Many in their wildness refused to leave the boat, but begged to be allowed to perish in the flames, and when ordered into the life-boats would cling to the steamer until torn away by main force. There were six boats, the first leaving the steamer about 9 o’clock in the forenoon and the last about 2 in the afternoon. The captain was the last to leave the burning ship, and with the smoke and flames close upon him turned back to the danger, and with tears rolling down his cheeks waved his arms to the lurid tongues of the fire fiend.

The experience in the lifeboats was terrible. The air was cold and snow was falling, while a tempest raged upon the sea. The men in the boats were kept busy bailing out the water. The three engineers who had been badly burned sat in the boats while the salt water washed over their unprotected wounds. Thus the day was passed, and when night came the scene was more weird than ever. The mass of flames from the cargo of gin on the burning boat burned with a sulphureous blue at the bottom and a blood-red at the top, lighting up the sea for miles around. Indeed, so bright was the light that the captain and crew of the steamer Rhine, about 7 o’clock in the evening and upwards of 40 miles from the scene of the disaster, saw the reflection in the sky. The engines of the Rhine were at once opened wide and she bore down on the source of the light, reaching the burning ship about 9 o’clock.

Then another scene of wildest excitement transpired. On account of the rough sea, it was difficult to get the lifeboats up to the steamer, and take the half-frozen and exhausted passengers aboard the Rhine. Six of them fell back into the sea as they were being raised but were rescued by members of the crew of the Maasdam, who had all shown the utmost coolness and the most gallant bravery. One woman had her arm crushed between the lifeboat and the rescuing steamer. Not until 11 o’clock that night was the last lifeboat found, and the last one of the castaways brought aboard the Rhine to be cared for and made as comfortable as possible by their rescuers. By the consummate coolness and courage of the captain of the Maasdam, not a soul had been lost, and his name is honored by all who passed through the terrible ordeal.

Some additional information and interviews were also found in the Saturday morning Los Angeles Daily Herald Nov. 1, 1884.

Captain H. C. Vanderzee of the ill-fated Maasdam reported: “We left Rotterdam Oct. 18 with eight cabin and 143 steerage passengers and a crew of 45 men. All went well until the 23rd, when we encountered a violent gale, during which the petroleum tank located under the bridge on the upper deck commenced leaking. The next day at 2 p.m., Denver, one of the crewmen, went with a light in the oilroom to make an examination. A moment afterward an explosion was heard and the sailor, with burned face and beard, rushed on deck crying “Fire, fire!” Every effort to control the fire was useless. About 4 p.m. I ordered all hands into the boats. We could save nothing of the cargo or of our private property. Only the clothes we stood in could we take away with us. There was a heavy sea running all the time. The passengers created little or no confusion. I think they were too much frightened, and justly so, to do anything but obey orders. At 9 p.m. we were picked up by the steamer “Rhine”.

“There were 35 persons in each boat”, said Dr. Smith. “We remained near the burning ship, hoping that some vessel would see the light and come to the rescue. The flames burst from the ship aft first. The masts fell at five o’clock. The conflagration was a grand sight, but not appreciated at the time. I couldn’t even save my instruments. There was something ludicrous even in our dilemma. We had a pair of lovers in our boat and the man could not be induced, nor would the girl permit him, to take his arm from her waist to stand his turn at an oar.”

Heinrich Wolff, a passenger, said: “Officers and crew did all they could to save the vessel, but the steam pumps could not be gotten to on account of the heat. When the Rheine picked us up, our boats were being tossed about at a lively rate and were half filled with water.”

Bruns Peterman, First Officer of the German Steamer Rheine, was the man to spy what he thought to be a fire away in the distance and climbed to the top masthead to make it out. It seemed to be a ship on fire, about twelve miles to the southwest. The Rhine was promptly headed for the light. She took about an hour to get to it. The flames lit up the sea for five miles around. The signal lights in the lifeboats were soon seen and the boats got alongside, ropes were lowered and the people hauled on board. The women and children had to be taken up in baskets.

“The sea was very rough,” said Mr. Peterman, “and a severe storm came up at midnight. Had we been two hours later in getting to the burning ship, not a soul of the Maasdam’s passengers or crew would have been saved.”

Additional information from the New York Arriving Passenger & Crew Lists indicates the German Vessel Rhine arrived at Hoboken, New York Oct. 31, 1884. The following names were listed among the passengers: Abraham Sant, age 57; Abraham Sant, age 35; Edward Boardwell, age 29.

The two Sants listed were father and son, who were both born in Holland (Netherlands). Edward A. Boardwell was born in Wisconsin. He was a son-in-law/brother-in-law as he had married Barbara Sant around 1883-84. She was expecting their first child (a girl) in December 1884. Boardwell had two more daughters before moving to Wisconsin by 1900 where he worked as a Maine Engineer. He died in Wisconsin in December 1915.

Son Abe Sant (Jr.) married Amelia Kling in Montague, in December 1885.They had three children, only one living to adulthood. In 1892 Abe was appointed Undersheriff for Menominee County, so they moved to Menominee City. By the 1900 census, they were back in Montague. The 1910 census showed they were living in Muskegon where he was the Deputy Sheriff. He died in Muskegon in July 1910.

Abram Sant (Sr.) married Cornelia Slinger in Holland and they had three children. By 1870 they had arrived in the US and were living in Spring Lake. In 1880 they were living in Montague, where Abram was listed as a blacksmith. A city directory listing for 1887-90 indicated he was still a blacksmith and was now living in the Montague House, as his wife had passed away in 1883. No other information could be found about Abram Sant.

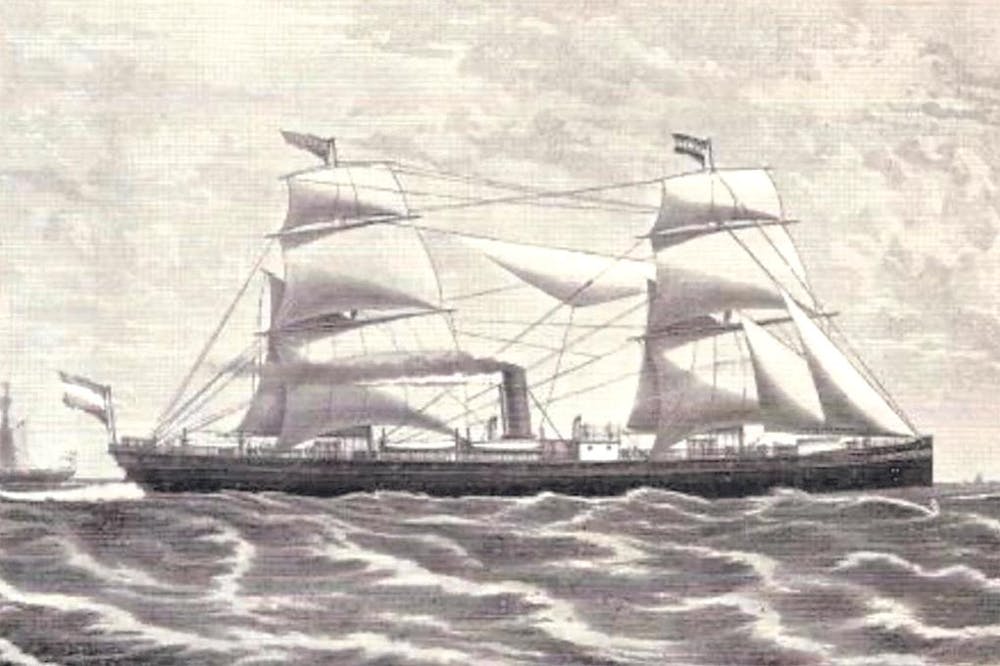

The Maasdam sailed for the Holland-America Line from 1883-84. It was built by Henderson, Coulborn & Co., Glasgow, Scotland in 1872. Dimensions: 255 feet by 35 feet. Propulsion: Single-screw, 10 knots. Compound engines. Masts and Funnels: Two masts and one funnel. Accommodations: 8 first-class and 388 third-class passengers, with a crew of 46. It was destroyed by fire at sea while on a voyage from Rotterdam to New York, Oct. 24, 1884.